Misleading: ‘Fake Chinese sea cucumber’ videos actually show vegan food and chocolate dessert

In mid-November 2025, a post in Korean on X shared a video purportedly showing “fake” sea cucumbers in China. The clip and its subtitles detail how the fraudulent products are made from start to finish, with ingredients listed.

The post received more than 290 likes and 156 shares, with many comments in Korean criticizing China for manufacturing fake seafood. The same video was also shared on Douyin two weeks earlier. This version gained over 41,100 likes and more than 120,000 shares with similar claims.

In China, food fraud and related safety issues have long been a concern, with recurring cases involving counterfeit, substandard, or artificial food products, such as eggs produced with industrial chemicals and additives.

However, Annie Lab found that the viral video conflates footage of vegan and synthetic sea cucumbers, which are established seafood alternatives and are marketed as such.

Plant-based dishes that deliberately mimic meat have long existed in Chinese cuisine, driven not only by religious practices but also by the historical difficulty of sourcing certain animal ingredients. Additionally, known imitation sea cucumbers do not necessarily raise food safety concerns.

In the viral Douyin video, most of the footage genuinely shows the making of an imitation sea cucumber or a mold, but it also includes dessert-making clips unrelated to sea cucumbers.

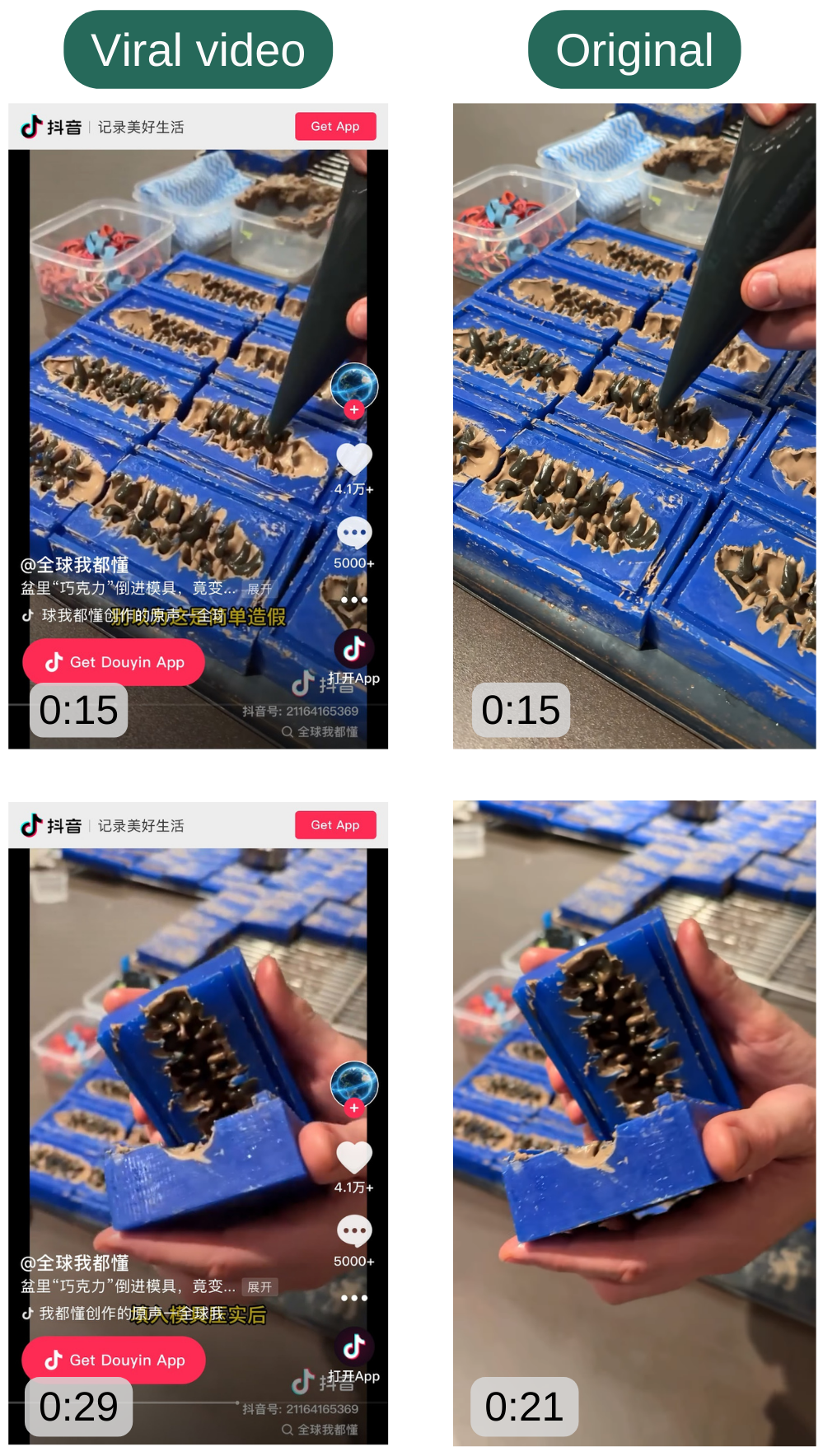

Two segments, which appeared in the first 15 seconds and again from 0:25 to 0:33, seemed to have been lifted from an Instagram reel posted by a restaurant guide account. The reel shows the making of “The Banksia Pop,” a signature dessert at Yiaga, a fine-dining restaurant in Australia.

According to the reel’s description, the outer shell of the dessert, which resembles the soft spines of a sea cucumber’s cylindrical body, is made of chocolate and cocoa butter. It has no connection to vegan or synthetic sea cucumbers. The segment from 0:25 to 0:33, in particular, shows the molds used to make the dessert.

From 0:16 onward, the viral video collage uses footage taken from a recipe video posted on Douyin by a creator who focuses on food safety awareness and exposé. Segments providing step-by-step instructions for mixing ingredients such as flour, konjac, and additives for flavor, visual appeal, and texture to make imitation sea cucumbers were edited into the video.

Some important on-screen text from the original recipe video was removed in the misleading clip.

For example, at 0:09 of the original (corresponding to 0:18 in the viral clip), the creator listed key ingredients in the top-left corner and provided a detailed description of how imitation sea cucumbers are made. A disclaimer in the top-right corner stated that the recipe was for entertainment purposes only and that the items shown were props used in a skit.

But those explanations appeared to have been digitally removed from the compiled viral video.

Meanwhile, from 0:34 to 0:40, the viral video incorporates footage from another Douyin post by an industrial food processing machinery supplier advertising silicone molds used to produce vegan sea cucumbers.

The ad says these molds are designed to closely replicate real sea cucumbers, adding that “sea cucumbers do not always have to come from the sea” with such hashtags as “vegan sea cucumber mold” and “vegan sea cucumber.” The ad video was later deleted and is no longer available online.

Imitation sea cucumbers in Chinese culinary culture

Vegan sea cucumber, often made from the konjac plant, is emerging as an alternative delicacy across East Asia, particularly in China. Some manufacturers (archived here) blend konjac flour, tapioca starch, and bamboo charcoal to mimic the chewiness and appearance of traditional sea cucumber, while Hong Kong and Taiwanese producers (see examples here and here) have introduced ready-to-cook versions to hotpot restaurants and supermarkets.

These vegan alternatives appeal to health-conscious customers and vegetarians who want familiar flavors without the environmental cost associated with wild harvesting.

This interest in konjac-based sea cucumber fits into a much older Chinese tradition of crafting plant-based mock meat products, a culinary lineage that links vegetarian eating to health, religion and refinement.

According to the Beijing Municipal Cultural Heritage Bureau (archived here), kitchens from ordinary homes to temples and imperial courts have used soybeans, konjac, wheat gluten, and vegetables for centuries to imitate meat and fish in both form and flavor.

Vegan meat, along with broader vegan cuisine, was developed during the Tang and Song dynasties, with records in historical texts describing “roasted meat” made from dough and konjac.

Today’s vegan products, though shaped by modern concerns about wellness and sustainability, continue this long cultural practice of creating plant-based versions of classic dishes.

Another type of synthetic sea cucumber, albeit less common on the market, is made from small pieces of actual sea cucumber left over from pre-processing, combined with gelling agents to replicate the texture and appearance of authentic whole sea cucumbers.

According to a patent application (archived here) granted by the China National Intellectual Property Administration, these products can be made using several methods, including hot casting with agar-based gels, electroforming with seaweed-derived materials and metal molds, and ionic gelation using sodium alginate and calcium chloride to create structured hydrogels.

Sea cucumbers and food safety concerns

Food safety concerns in Mainland China, shaped by scandals such as the 2008 melamine-tainted infant formula and “gutter oil”, have heightened public suspicion toward unfamiliar or “engineered” food, including synthetic sea cucumbers.

In response, authorities and industry have introduced more guidelines for plant-based and vegan food to push for clearer standards and ingredient-disclosure labeling, aiming to help consumers distinguish legally produced, technically processed products from unsafe or fraudulent ones.

Confusion and deception have nevertheless been reported in the market. In 2016, the China National Radio said (archived here) vegan sea cucumbers were sold without clear labels, misleading consumers into believing they were traditional animal-based products. A merchandiser later admitted to the reporter that the sea cucumbers in question were vegan, underscoring concerns about transparency.

The report also outlined ways to tell genuine sea cucumbers from synthetic ones. Real sea cucumbers are typically brown or dark brown, with uneven, elastic spines and fibrous traces inside after gutting. Synthetic versions tend to be glossy black, lose color when soaked, have uniform and brittle spines, and a smooth, sealed interior.